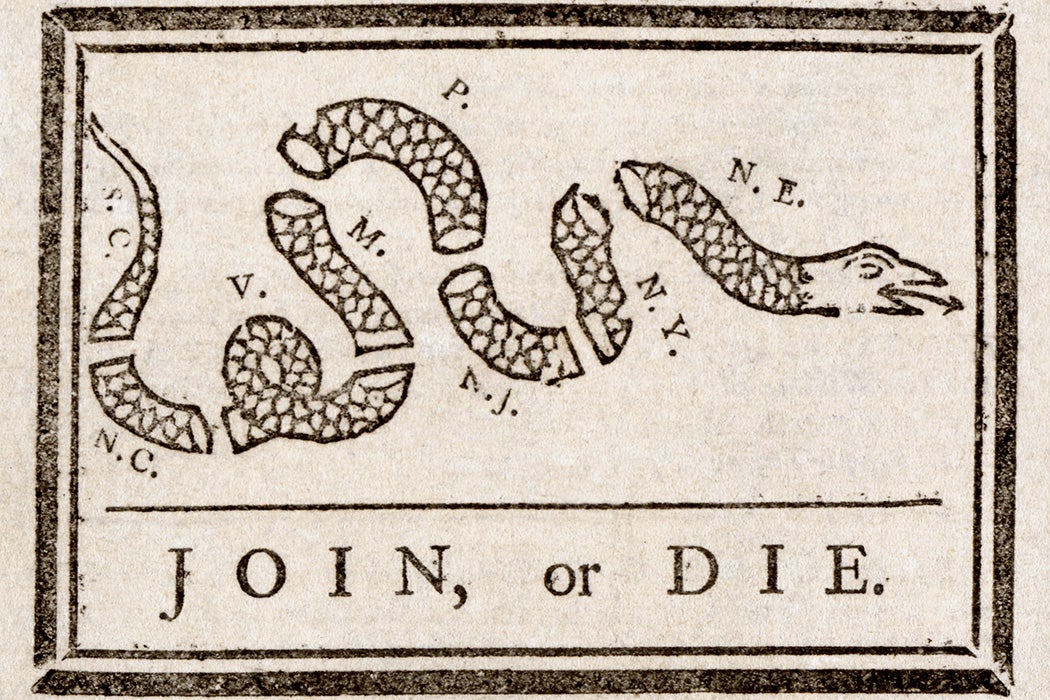

“The uniquely New World rattlesnake is one of a handful of animals that might be said to have its own historiography,” writes historian Whitney Barlow Robles. Much of that historiography is about rattlesnakes as “cultural products of the human mind,” particularly as symbols of revolution in the colonial period. In fact, continues Robles, “snake symbolism and figurative rattlesnakes have proven so potent in the historical memory of early America that scholars have often overlooked the actual creatures.”

The timber rattlesnake, Crotalus horridus, was found throughout the eastern half of North America when Europeans arrived. Settlers were gobsmacked by them. In 1630 Puritan Francis Higginson described “Serpents called Rattle Snakes, that haue Rattles in their Tayles that will not flye from a Man as others will, but will flye vpon him and sting him so mortally, that he will dye within a quarter of an houre after.” A century later, naturalist Mark Catesby called the rattlesnake the “most formidable [of the serpents], being the largest and most terrible.”

“Rattlesnakes confounded the efforts of European scientists and settlers to understand American nature and to conquer and colonized American landscapes,” explains Robles. Naturalist balked at exploration because of the “Danger of Rattlesnakes.” Indeed, the snakes were something of a check on European expansion—poet, playwright, and naturalist Oliver Goldsmith (1774) even called them “centinels to deter mankind from spreading too widely.” The survey of the disputed boundary between Virginia and North Carolina in 1728, for instance, was delayed for months because of the fear of rattlers.

More to Explore

The Serpents of Liberty

Robles calls the animals “both hyper visible and nearly invisible, equal parts powerful and vulnerable.” They’re certainly venomous—the fatality rate today is about 1 in 600 bites—but they’re also fairly docile, generally only biting when provoked. After all, they warn before they strike. Their “unique nature thwarted the knowledge gathering and surveying efforts of Europeans and settlers on personal, scientific, and imperial levels, even as colonists embraced the animal’s potential as a formidable symbol.”

Ignorance about rattlers “could be a cause for celebration and a means of self-preservation in the case of wary Europeans, where avoiding knowledge of rattlesnakes yielded physical safety,” Robles proposes. The maraca-like rattle was seen as providential by Puritans: a gift from God warning of the approach of danger. Made up of a series of hollow, interlocking keratin segments, the rattle is unique to the Crotalus genus; plenty of snakes shake their tails in warning, but only rattlesnakes rattle while doing so.

Ultimately, alerting humans to their presence might not have been the best approach for the rattlers. As Robles writes,

[t]he chasm between the rattlesnake as a useful symbol and the rattlesnake as a potent animal ultimately could not be bridged, and settlers turned to crushing the heads of serpents in biblical fashion even as they housed rattlesnake flags above their heads. The transformation of the rattlesnake into a colonial icon coincided with the demise of the snakes themselves as settlers began to bludgeon rattlesnakes by the thousands.

Eighteenth-century naturalists debated the concept of extinction even as rattlers—like Native Americans—were driven out of existence in many areas via bounties, community-wide kill-a-thons, and militias. Places named after rattlesnakes soon had no rattlesnakes, and to this day, Maine, Rhode Island, Delaware, Michigan, Ontario, and Quebec no longer have rattlesnakes. The species is endangered in Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Virginia, and New Jersey, and threatened or of special concern in many other states.

Weekly Newsletter

Meanwhile, Native Americans worked to protect rattlers from settlers bent on hunting them to extinction. The “logic of elimination” of settler-colonialism encompassed the native animals as well as the native people. Native Americans kept secret the location of hibernacula, the underground chambers in which clusters of rattlesnakes—sometimes hundreds of them—overwinter. (Europeans had learned that the best way to kill snakes was to attack when the snakes emerged in the spring.) To this day, conservationists follow the Indigenous practice of not publicly revealing the locations of hibernacula to protect them from contemporary snake-killers.

Robles, who includes rattlesnakes in her book Curious Species: How Animals Made Natural History (2023), notes that the social lives of rattlers were largely unknown even to scientists until quite recently. This means scientists are just catching up with Native Americans who understood “underworld communities of rattlesnakes as bona finds snake societies” intermeshed with human societies through mutual obligations.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.