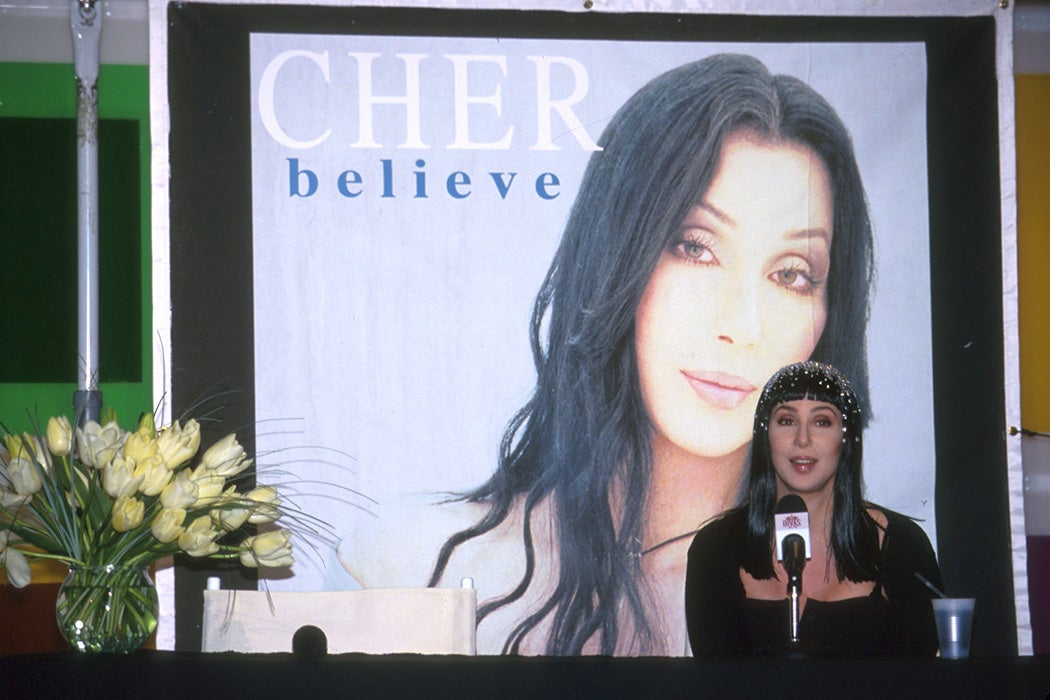

Cher kept a low profile for a few years in the 1990s, navigating career shifts and personal challenges, before she erupted in the fall of 1998 with the futuristic Eurodance track “Believe,” the title track of the eponymous album.

Other than the philosophical nature of the lyrics (“Do you believe in life after love?”) and the propulsive beat, what made the song stand out was its “talking robot” effect. Whether it was created with a vocoder or with the autotune software (the producers were always fairly coy about it), “[t]he vocoder effect—which arguably snagged the track such widespread popularity—grew into one of the safest, maybe laziest, means of guaranteeing chart success,” writes Kay Dickinson in Popular Music.

In those years, several notable tracks featured a timbre-modifying effect: Eiffel 65’s “Blue (Da Ba Dee),” Sonique’s “It Feels So Good,” Madonna’s “Music,” Victoria Beckham’s “Out of Your Mind” (with the help of True Steppers and Dane Bowers), Steps’ “Summer of Love,” and the back-up vocals in Kylie Minogue’s “Spinning Around” are some of the more well-known examples.

Originally a military device usually employed to disguise military transmissions, the vocoder was adopted by musicians with heavy investments in types of futurism, including Kraftwerk, Stevie Wonder, Devo, Jean-Michel Jarre, Cabaret Voltaire, and Laurie Anderson.

“Later, the vocoder became a stalwart technology of early electro and has, since then, infused contemporary hip hop and the work of more retro-tinged dance acts such as Daft Punk and Air,” notes Dickinson, adding that it did experience some decline in popularity between the mid-1980s and the late 1990s.

The use of vocoder fosters a discourse on performance, artifice, and camp.

“Vocoder tracks propose a dichotomy between the vocoded voice and the more ‘organic’ one, which then crumbles under closer inspection, most obviously because both are presented as exuding from the same human source-point,” writes Dickinson. “In vocoder tracks, the vitality and creativity inherent in the technologies in use stand centre stage, pontificating on questions of authenticity and immediacy.”

Detractors shrug it off as gimmickry because, at the turn of the millennium, it was associated with pop music.

“Taking the issue of pop further, it also becomes difficult to bypass entrenched systems of expertise and work as they reside within not only authenticity, but also artistic polish and effortlessness (or perhaps lack thereof) within respectable and respected music,” writes Dickinson. “The vocoder, after all, is often seen as a sparkly bauble which distracts us from a lack of talent hiding ‘underneath.’”

Additionally, for many female-identifying music stars, Dickinson observes that their own body is their instrument. Even so,

the vocoder effect, however it is produced (and even by whom), impairs the “naturalism” of the female voice not by ignoring it, but by creating the illusion of rummaging around inside it with an inorganic probe, confusing its listener as to its origin, its interior, and its surface.

Cher’s “Believe” occupies an interesting position because it combines the instrumental qualities of dance and techno but plots out its vocal aesthetic differently.

“Its instrumental timbres,” writes Dickinson

which have very little grounding in “traditional”/non-computer-generated instrumentation, evoke the trancier end of techno. Shorter sci-fi stabs meet surging upward flourishes which also link Believe stylistically to disco and Hi-NRG, associating the track with certain gay subcultural histories.

However, unlike most dance music, “Believe” is also very song-like, in that vocals are uncharacteristically high in the mix, as they would be in a pop track.

More to Explore

Tape Heads

“The song is solidly ‘Cher’ and, although Cher is not solidly organic or singular as a site of production, she is still a star persona, a firm identity to which much of the song’s meaning can be attributed, however speculatively,” writes Dickinson.

On this note, the vocoder also hints at queer subculture. Eiffel 65 used it for “Blue,” a track on their album titled Europop, “in reverence to a musical style not usually associated with heterosexual masculinity,” notes Dickinson. Its usage by the likes of Madonna and Kylie Minogue, LGBTQ+ icons in their own right, also cements the association of vocoder-enhanced pop with queer euphoria.

And indeed, “Believe” is also an important gay anthem because, performer aside, it invokes themes familiar to gay dance classics, namely the triumph and liberation of the downtrodden or unloved. “This song is a bittersweet declaration of strength after a break-up and, by saying ‘maybe I’m too good for you’, Cher conjures up certain allusions to the vocabularies of gay pride,” writes Dickinson.

Weekly Newsletter

Finally, it’s easy to see Cher’s use of the vocoder as camp.

“One of camp’s more pervasive projects is a certain delight in the inauthentic,” Dickinson writes,

in things which are obviously pretending to be what they are not and which might, to some degree, speak of the difficulties of existing within an ill-fitting public facade—something which evidently concerns “Believe.” […] Camp has always been about making do within the mainstream, twisting it, adoring aspects of it regardless, wobbling its more restrictive given meanings—something which this reading of the vocoder undoubtedly does too.

The vocoder started out as a tool for masking, but in the decades since, it’s developed into a tool for revealing what might otherwise remain hidden, aurally or culturally.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.